[ad_1]

On November 1st, Canada announced that it would be keeping immigration levels constant, hoping to welcome roughly 500,000 immigrants a year, in 2025 and 2026.

While Canada’s current immigration levels are already at record-breaking highs, a recent report from the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) suggests that immigration levels will likely need to rise again soon; further stating that Canada’s immigration rates, as they currently stand, will simply not be enough to uphold the country’s population and meet domestic labour market demand.

The current situation

Canada needs immigration for several reasons—most pressingly to address concerns around the country’s demography and labour market.

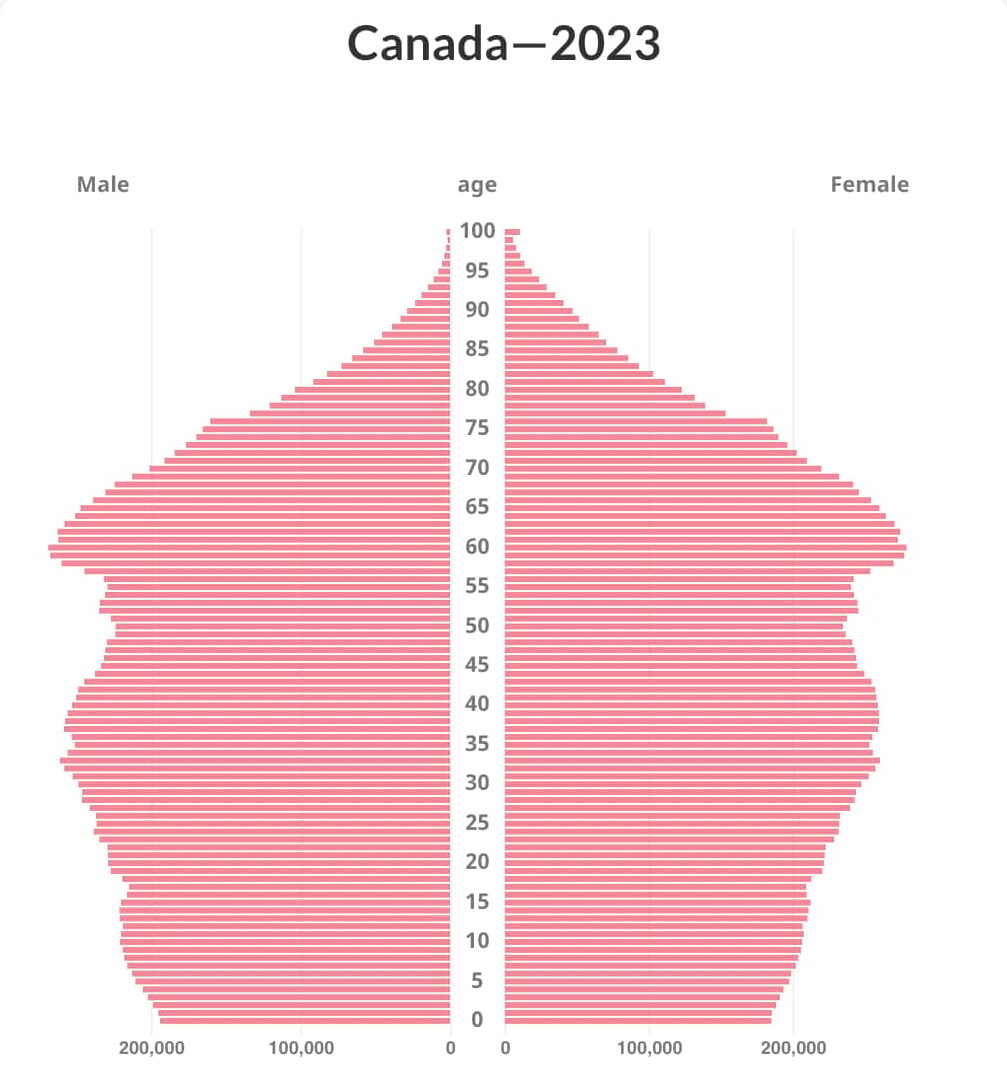

Canada has one of the world’s oldest populations, combined with a low-fertility rate (1.40 births per woman) that has come to currently typify many countries in the west. This combination of factors makes it impossible for Canada to replenish its population with just natural-born Canadians—making immigration crucial. Connected to this problem are further demands that Canada’s economy (the ninth largest in the world by Gross Domestic Product (GDP)) has on its labour market—which is impacted by the same replenishment problem that Canada’s population faces.

These two factors help underline the necessity of immigration to maintain Canada’s national health and prosperity in the future. Given this information, it would be reasonable to assume these are the reasons behind the record-breaking pace of immigration that can currently be seen in Canada. However, when considering the current stabilisation of immigration targets, this is only half the story.

Why immigration may need to rise again

Currently, immigration targets are set to normalise at 500,000 immigrants per year, until at least 2026. While this is a record-breaking number of newcomers welcomed annually (standing at roughly 1.3% of Canada’s current population), it is not enough to stabilise Canada’s population—and therefore further not enough to sustainably meet future labour demand.

According to RBC’s report, Canada would need an annual immigration rate equivalent to 2.1% of the current population—or 849,944 new permanent residents yearly (at the time of writing). This means that current immigration targets would have to increase by more than 300,000 annual immigrants in order to offset both the low fertility rate and the ageing population in Canada.

A Desjardins study released earlier in 2023 on the right amount of immigration for Canada noted similar findings. According to the report, not only would Canada have to ramp up its immigration efforts, but this would primarily have to be a function of growth in the working-age population (note that the 500,000-newcomer figure represents immigrants from all categories including family sponsorships and refugees). In the case of the Desjardins study (which also considered factored in Canada’s labour market and socialised healthcare infrastructure), annual growth of the working-age population would have to be at 2.2% annually (721,600 newcomers) to maintain current ratios of young to old working people; or by 4.5% annually (1,476,000 newcomers) to maintain the historic ratio of the working-aged to retired population.

Under both of these forecasts, Canada must continue to significantly increase its current immigration levels, not just for the sake of the country’s demography, but also to help meet labour demand, continue the growth of the economy, and support the country’s healthcare, infrastructure, and broader social institutions.

Canada’s population pyramid shows the country’s ageing demography

The need to stabilize levels between 2024-2026

Even though Canada’s long-term need for immigrants is well-noted, the RBC report argues IRCC’s decision to stabilise the current levels are also warranted.

Canada’s ability to welcome and integrate newcomers into its demography and economy is the key factor that will determine the overall success of its immigration program. In the wake of recent housing pains, the country’s ability to provide housing (not just new immigrants, but also Canadians) in an affordable manner has come under scrutiny—a fact that further has ignited further contention around the subject of immigration.

In response, IRCC has committed to readdressing the number of temporary residents (those on a study or work permit)—a category which saw a massive increase in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the federal government has committed to addressing key labour shortages in the construction sector (an area with persistent job vacancies) with balanced immigration that is reflective of the stabilised immigration targets—allowing for the balance between meeting labour shortages and increasing housing demand, that economists in Canada have been calling for.

[ad_2]